Making an electric car battery requires more than 60 kg of difficult-to-extract minerals. Upstream, at the very least, the green car is not without its environmental impact.

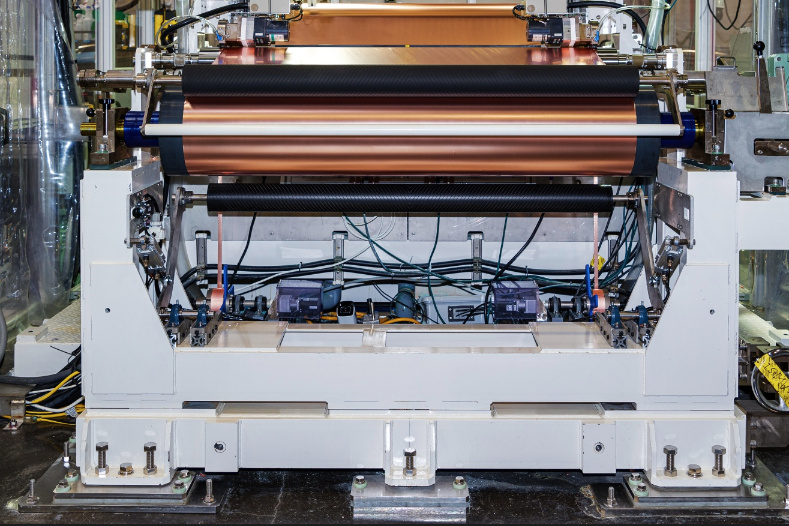

But recent breakthroughs in recycling are reducing its environmental footprint, as seen at US battery recycler Redwood Materials.

Mining the raw material and refining it requires enormous amounts of energy. Therefore, the carbon footprint of an electric vehicle when it leaves the factory exceeds that of a comparable traditional vehicle. These initial emissions are offset over time by the higher efficiency of the electric motor. The result: a 70% reduction in total emissions over the average life of the vehicle.

In the United States, the threshold where an electric vehicle becomes cleaner (in CO2 emissions) than a traditional vehicle is around 26,000 miles, according to BloombergNEF. But this calculation assumes that its battery was made with newly mined lithium, nickel and cobalt, as if all these precious metals end up in the landfill when the electric vehicle is sent to the scrapyard. But this is not the case. The new recycling industry recovers batteries.

Electric car recycling, which emerged very recently, is already profitable and recovers more than 95% of the main metals. According to a Stanford University study (still peer-reviewed), Redwood Materials’ recycling process produces up to 80% less CO2 than the traditional supply chain. This would bring the “net zero emissions” threshold of an electric vehicle to less than 15,000 km compared to its equivalent powered by an internal combustion engine. Beyond 15,000 km, each kilometer traveled is a gain.

The full assessment of the electric benefit depends on the type of energy used to make the battery and charge the vehicle. Cleaner electricity – such as Quebec hydroelectricity – increases this advantage, but even where electricity comes from coal, the electric vehicle eventually wins out.

The rise of renewable energies will make electric cars even less polluting. According to the International Energy Agency, global solar energy production has been on record growth for 22 consecutive years and appears to be accelerating.

According to the Stanford study, battery recycling consumes 79% less energy and emits 55% less CO2 than traditional refining. In addition, recycling is done locally, while the first extraction metals travel around the world. Closing the loop would reduce CO2 by 80%.

According to chemical engineer Will Tarpeh, who teaches at Stanford and co-authored the study, the benefit of recycling is only just beginning to be felt: Electric vehicles are new and only a small number have been sent to the scrapyard.

However, it is expected that the number of lithium-ion batteries recycled in 2024 should be double those that were manufactured in 2014. To establish the environmental footprint of electric vehicles, it is now necessary to measure the net footprint of the materials used, because recycling will have a growing impact.

The rise of recycling brings challenges and opportunities. Simplifying battery design will be crucial, Tarpeh believes.

Current processes adapt to current battery designs. “We are playing catch-up with the batteries already manufactured,” explains Mr. Tarpeh. Few designers consider recyclability when developing battery chemistry, but in my opinion, it’s starting to change. »